Colin Clark

Millennial creators are dealing with family trauma. We feel the weight of a mismanaged world thrust upon our shoulders, and we have something to say about it. Many of us don’t or didn’t handle it the best, but we strive forward every day to make it right. To right the wrongs of our parents, of our siblings, and mostly of ourselves. We refuse to let the cycle of generational trauma continue, so we take the burden upon ourselves to make it stop. Colorgrave’s Prodigal tells one such story. Oran Graille stole 400 gold from his family, and high-tailed it for the southern lands for reasons only he knows. A letter from his grandfather reaches him one day, telling of his parents’ untimely demise, and demanding he return home. Upon arriving at the docks of his hometown, he is berated by the seafarers and town dwellers he meets. Many remember him, and aren’t so keen on his return. River, in particular, really has it out for him. She respected his parents as guides and can’t fathom why he did what he did. She treats Oran to more than a cold shoulder, outwardly castigating him for his familial crimes. River can be found later, mourning at the Grailles’ graves. The meeting doesn’t go too well. The local sheriff has “no interest in locking [him] up,” but warns Oran to keep clear of trouble, also chastising him for the theft and departure. Every single one of the characters in Prodigal weighs in on Oran’s life choices. The opinions sit heavily on the player and become their own burden to carry. We are given only small “yes” or “no” options in a few bits of dialogue in which to make known our intentions, be they atonement or apathy. My Oran returned to Vann’s Point to make amends, though there are subtle options to keep your intentions closer to your vest, almost doubling down on your past life choices. In all honesty, I don’t know what comes of picking the more “negative” approaches to dialogue choices. Oran works his way, bit by bit, in atoning for prior sins: paying of the money he stole, working hard for the blacksmith-apprentice-come-replacement his grandfather has hired, and running two – that I’ve found – elaborate fetch and trade quests a-la Link’s Awakening for the villagers and the residents of the mysterious Colorless Void.

The villagers all take turns letting Oran know what they think of him. Some flirt, some rebuke, and some are downright hostile.

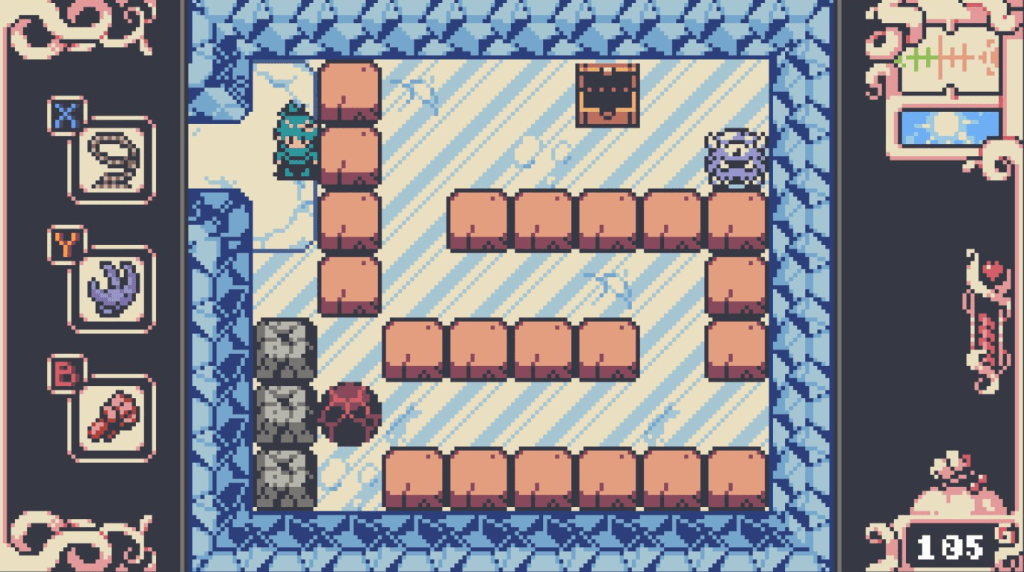

Prodigal brings much of its weight to the table through a rich tapestry of lore. This is the first indication I got that there was so much more lurking below the surface than a zelda-like adventure. There are multiple religions, ancient wars, rival factions, aged heroes, cursed swords, and ghost captains; most delivered to the player through interactable environments and dialogue. Books can be found on shelves and notes on desks. Secret rooms can be found and searched, and the contents of most drawers trigger unique slice-of-the-world text boxes. Almost everything you see can be checked, and almost everything adds to the world of Prodigal. A lot of thought has gone into world building, and this is what truly makes the game shine. Gameplay itself is a well refined top-down Zelda-like (my favorite), replete with puzzles and simple yet engagingly flexible combat. Oran’s pickaxe does the work of bashing bats and zombies magnificently, and you’re never punished for just missing your target. The game seems to say, “we know what you meant to do there, so we’re gonna give it to you!” Combat isn’t the main focus anyway, as enemies are simply another layer to the devilishly contrived puzzle dungeons. Each and every room after the first tutorial dungeon forced me to stop for a second and made my brain go “huh.” Most puzzles made me feel smart without frustrating me, even offering up a few towards the end that I bashed my skull against a few times until the solution became clear. For me, there were more times than I’d like to admit that I found the solution accidentally. Once those harder puzzle rooms clicked, however, the solution seemed so obvious that I definitely couldn’t hold it against Prodigal for making me think. Each dungeon brings a welcome new mechanic, and some can be done out of order; though you’d better be prepared to get hurt. Early on, Oran obtains three key items bound to the face buttons of the player’s controller. One teleports Oran directly to where he first entered the room, one is a lasso that has so many uses – hint: try putting the loop on some particularly frustrating enemies – and one is a power-glove that smashes giant boulders and rolls heavier objects. Between these three items and Oran’s pickaxe, the variation in puzzle design is near endless, and each room feels fresh.

Outside of and between dungeons, the player explores the world of Vann’s Point, a town full of vibrancy and life. Each character follows a daily schedule, and the town follows a morning-day-evening-night cycle where the residents go about their daily lives as Oran attempts to rebuild his own life amidst them. To say much on the story would be to spoil the magic. Each character builds upon their own unique personality. There is love and betrayal, conflict and sacrifice. Suffice it to say, Prodigal has done the work to build an engaging environment full of characters you want to know and spend time with. You rebuild and repair friendships, perform acts of service, and can even get married (to any of TEN different characters!). There’s far more to Prodigal than the Zelda clone it seems to be at first glance. Had I played it in 2020, it would’ve sat very near the top of my GOTY list. I’m just glad I finally did find it.

If you’ve ever felt the odd one out of your family, shunned for your mistakes, burdened by the decisions of your forebears, or maybe you find yourself trying to make amends to those around you for past transgressions, Prodigal has something to say to you. It might not be a comfortable process, but its message is kind, its puzzles fulfilling, and its charm endless. It is everything I’ve ever wanted out of the genre, and more. You can pick up Prodigal from Colorgrave here.

AND WHAT’S THIS?! THERE’S A SEQUEL IN THE WORKS?!

The fourth-wall-breaking, amazingly enthralling demo for Veritus can be found here. It is made even more special to those who have played its predecessor. I played them out of order. Don’t tell on me.

Leave a comment